Indonesian Lesson 4: Pronouns

Creating Indonesian lessons is actually much more difficult than I expected! It’s a very simple language to speak, but when you start getting into the nitty gritty of the culture and how to speak properly, or in formal situations, or how to write it well, it gets really tricky. So, those of you who are really wanting to learn Indonesian well without waiting for me to create lessons, here is a book that you can buy off of Amazon that has good reviews and includes an audio that you can download:

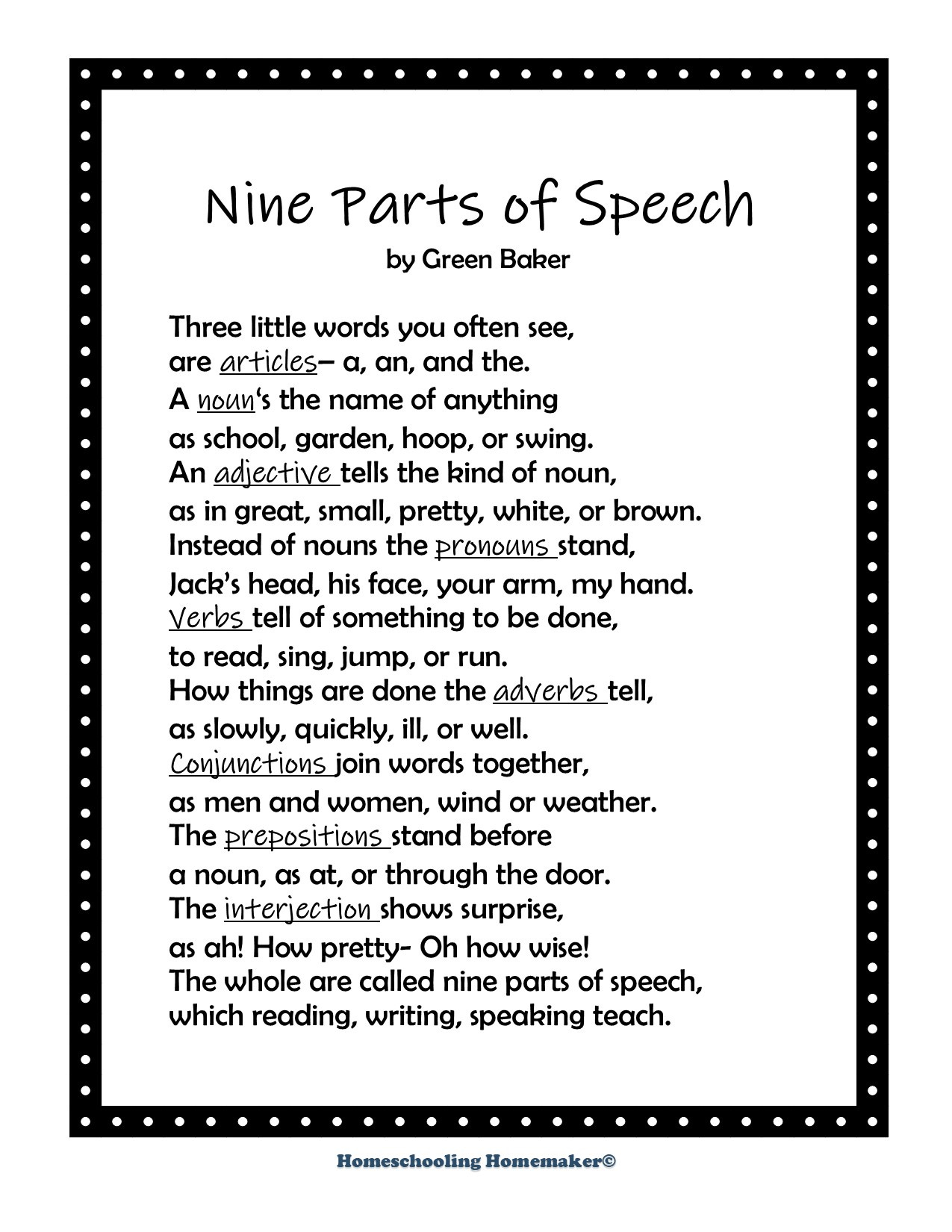

For the rest of you, here we go! Grammar is the mathematics of words. It explains how a specific language works, and includes both the nine parts of speech as well as sentence syntax. In case you need to brush up on your nine parts of speech here is a handy poem written by a student named Green Baker in the 1800s (you can right click and “save image as” if you would like to print it out):

Fortunately, the Indonesian language doesn’t use articles, so you can mark that part of speech off as “learned.”

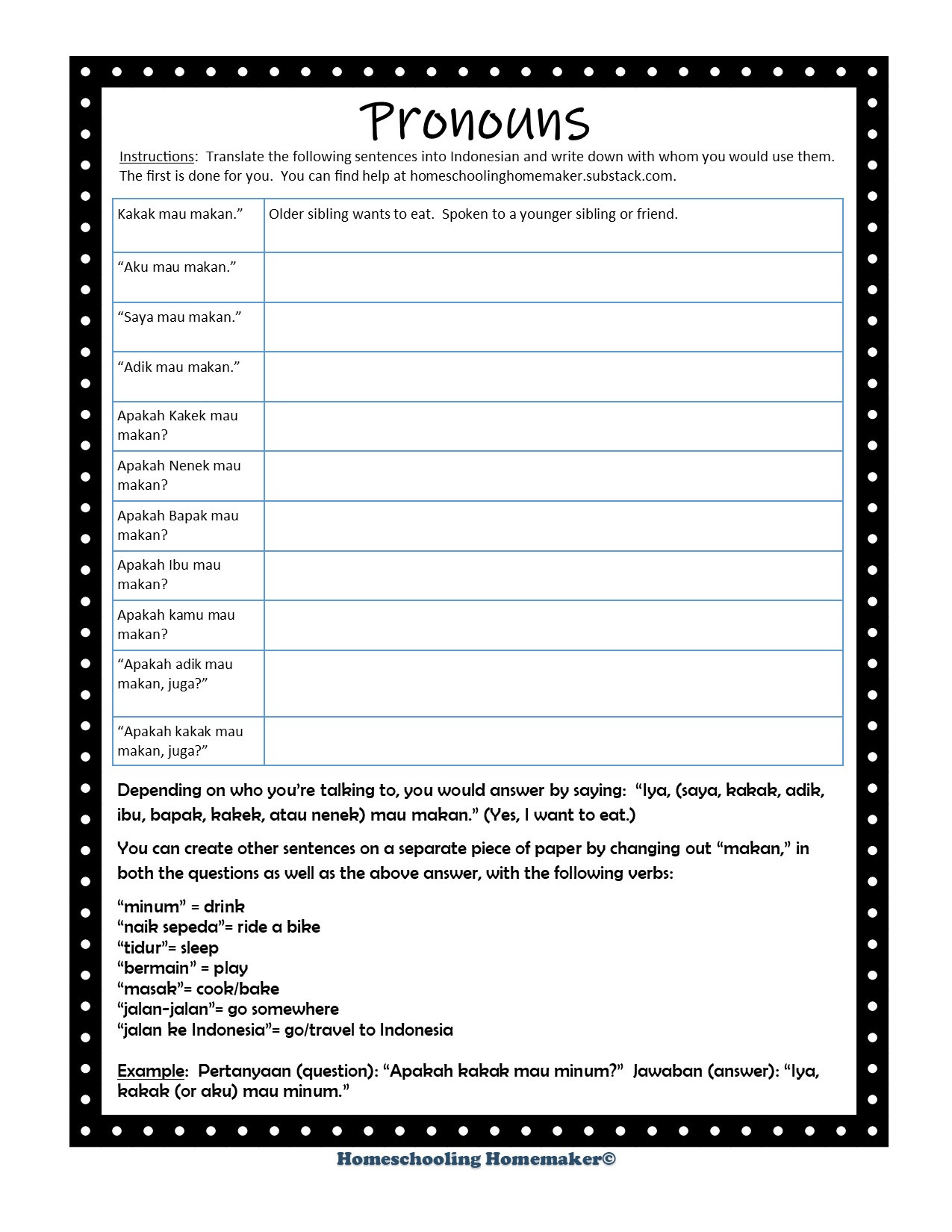

Pronouns in Indonesian are a little bit difficult, but we’ll start out with the basics (you can right click and “save image as” if you want to print it out to use):

According to my Indonesian Grammar Made Easy book, the word “Anda” was invented in the 1950s to be used as “you” in both formal as well as informal situations, so just keep that in mind while I try to explain how pronouns actually work here.

In my own experience people use “Anda” mostly on television and when preaching or leading meetings. Even then, it always sounds strange. This is because Indonesian uses different pronouns for the same person (I and you) based on who you’re speaking with. You may even use your own name or the person’s name that you’re talking with instead of “you,” in order to be polite. This took me so long to figure out! It just was too weird to use my own name instead of “I” when speaking about myself. I still don’t actually do this, though, but that’s probably because in the area where I live in Indonesia it's not that important! Speaking of which, Indonesian is an interesting language because it is greatly influenced by the local language where it is being spoken. So, in some areas, like in Java, where the local languages, Javanese and Sundanese, actually have whole different levels of language based on who you're talking to and your station in life, speaking formal/polite Indonesian is much more important than Kalimantan, where I live.

So, this is how the pronoun “you” actually works:

“Kakek” means “grandfather” and is used to address your grandfather or someone the same age as your grandfather, especially any older male relative, such as your great uncles.

Example, asking your grandfather if he wants to eat: “Apakah Kakek mau makan?”

“Nenek” means “grandmother” and is used to address your grandmother, or someone the same age as your grandmother, especially any older female relative, such as your great aunts.

Example, asking your grandmother if she wants to eat: “Apakah Nenek mau makan?”

“Bapak” means “father” and is used to address your father or any man the same age as your father. You can also shorten it to “Pak” or use it as “Mister” as in “Pak George.” Married men with children are often called by their eldest child’s name. Most people call my husband “Bapak Mulia.”

Example, asking your father if he wants to eat: “Apakah Bapak mau makan?”

“Ibu” means “mother” and is used to address your mother or any woman the same age as your mother. If you’re a married woman and have children, you are called by your eldest child’s name. So, since I’m married and have an eldest child, most people here call me “Mama Mulia.” Most people here use “Mama” instead of “Ibu,” but I’m not sure that it’s like that everywhere in Indonesia. If in doubt, use “Ibu” instead.

“Kakak” is used to speak to an older sibling or for yourself instead of “I,” if you’re older, or to address an older person and/or “adik” can be used for yourself if you’re the younger sibling or to address someone who is younger.

For example if you’re asking a younger sibling if they want to eat with you:

“Kakak mau makan. Apakah adik mau makan, juga?”

(Older sibling wants to eat. Does younger sibling want to eat, too?”

Or, you could say:

“Aku mau makan. Apakah adik mau makan, juga?”

(I informal want to eat. Does younger sibling want to eat, too?)

For example of you’re the younger sibling asking your older sibling if he/she wants to eat:

“Adik mau makan. Apakah kakak mau makan juga?”

Younger sibling wants to eat. Does older sibling want to eat, too?

Besides using your own name, there are two words for the pronoun “I,” which are “aku,” the informal word for “I,” and “saya” the formal word for “I.” Here are examples of how you would say “I want to eat,” based on who you’re speaking with:

Speaking to someone older than you:

“Saya (I, formal) or Your name (really formal) mau (wants) makan (to eat).”

Speaking to someone younger than you:

“Aku (I, informal), or Kakak (older sibling/friend), or Ibu/Bapak (mother/father or older woman/man) mau (wants) makan (to eat).”

Speaking to someone who you do not know well:

“Saya (I, formal) or Your Name (very formal) mau (want) makan (to eat).”

Asking someone older than you if he/she wants to eat:

Apakah Kakek mau makan?

Apakah Nenek mau makan?

Apakah Bapak mau makan?

Apakah Ibu mau makan?

Asking a friend if he/she wants to eat:

Apakah kamu (you informal or use person’s name) mau makan?

There are actually other ones, including ones from the Javanese language, because they’re everywhere in Indonesia so everyone talks to them using the Javanese terms. There’s also a Chinese term for “Ibu” that a lot of people use when speaking to Chinese Indonesians. It’s all very confusing, until it all the sudden makes sense!

Or, if you just want the basics, remember that you can use “saya,” which is formal “I,” and “Anda,” which is formal “you” in any situation. Using “Anda” all of the time will just sound a little funny, but it does work.

If you haven’t noticed, one easy thing about a lot of Indonesian pronouns and other terms is that they’re gender neutral! So, instead of “he, she, it,” you have “dia.” Instead of “him, her, it,” you have “dia” or the suffix “-nya” added to the thing possessed, which also can be used for “their.”

I’ve probably confused you enough for now. Hopefully you can work through everything and figure it out. I’m going to attach a worksheet below that you can have your students translate into Indonesian. I’ll provide the answers along with a recording of what all of the words sound like as well as more practice in my next Indonesian post.

If you have any suggestions for situations that you’d like to learn about in Indonesian, or ideas for improvements, please leave a comment!